Stonecoast Review

The Literary Journal of the Stonecoast MFA

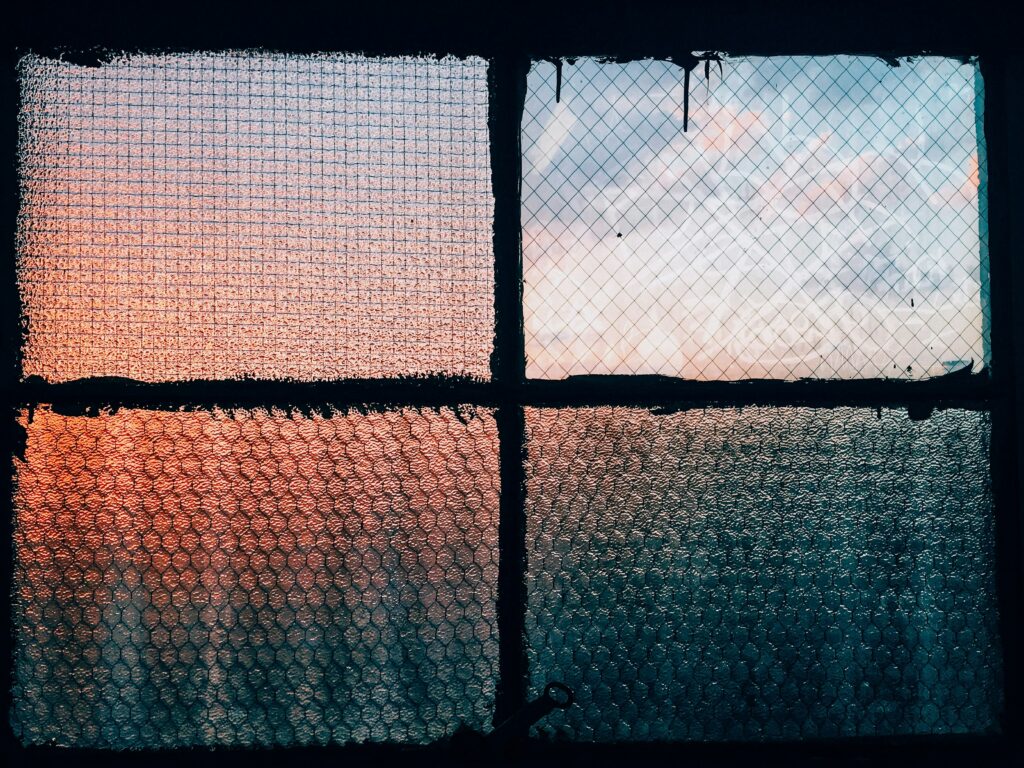

Frosted Glass

By Oona McPhearson

The sky was flat. And white. It looked like frosted glass. Adaline had always hated frosted glass. It was so very cheap, only ever used in mall bathrooms and ugly hotels; it was un-classy.

“How long have you been a ghost, if you can remember?” asked the woman.

Adaline didn’t look again at the woman when she answered. She could remember her face exactly. She knew she should more aptly be called a girl due to her obviously young age, but that lent her face too much innocence, so Adaline called her a woman.

“A long time,” Adaline replied. She continued to watch the frosted-glass sky. As far as skies go, it wasn’t a bad one, but it simply had to be frosted glass, didn’t it?

The woman’s hair was thin and average and brown. It hung in sticks down the sides of her face, cracked and tangled into a pretense of a bun. There wasn’t quite enough hair to begin with, and so the bun could not properly be called a bun, although it tried.

“Do you remember how you died, and when?”

“Yes.”

The woman looked up from her notepad. It was the first time she had done so since the beginning of the interview. Her skin was too thin. It was like a single layer of baklava, wetted and draped over her face so that there was nowhere it fit quite right. Her eyes unsettled Adaline. They were expressionless. It was not that their expression was unreadable, or hidden; they could not even be called empty, because that may have implied that they had once had an expression. They held, simply, nothing. It was neither good nor bad; there was not a single judgment.

Eye shouldn’t look that way, Adaline thought. Eyes should reflect a person’s insides. This woman had no insides.

“Would you care to elaborate?” the woman asked.

Adaline would have liked to describe her as mousey because of her hair and her skin, but because of her eyes she could not. This woman held a strange presence. It was silent, but it was in no way quiet. She looked down at the top of her mousy head, the woman’s eyes hidden by her feathered hair.

“I was shot at a ball that my cousin held. The shot was most likely meant for him. He was a radical and was equally hated as revered. Well, I say equally, but it must not have been, for someone to shoot at him.”

“Did you take the bullet for him, so that he could live?”

The woman did not lean forward, her eyes did not brighten, and this was why Adaline could not call her a girl, no matter that she could be no older than sixteen. She did not care for the world about her. She did not see it. She did not even see Adaline, for all she had been sent to interview her.

“No,” said Adaline.

The woman wrote this down, too. She looked up once more. Adaline did not turn away from her eyes this time. “Did you get to watch your funeral?”

“Yes.”

Adaline noticed a paper butterfly by the woman’s elbow. It was white, but in such a way that it did not exactly look like it could have been made of paper.

“What was it like?”

Adaline remembered only impressions. It had not been sunny, but she could not tell the woman whether it had rained. There had been white roses. The grass had been green. The sky had been frosted glass. “No one cried. Too many people came, so they overflowed the parking lot, and it was in the newspapers everywhere. Someone shot my cousin, and the other ladies got to say they’d seen both of us die.”

The woman wrote everything down. Her hand was small and looked to be of wax paper. The butterfly landed on her knuckles. It was blue now. Adaline wondered whether the woman could feel it. She made no reaction, and Adaline thought about why people could see her but not her butterflies. She had made hundreds while alive, so everyone could see them, back when they didn’t see her. Why had she been worthless, alive, interesting only now that she was considered a myth? When she followed her cousin up to society, she’d stopped making the butterflies. They followed her now, while she waited in death.

“Have you ever seen your cousin, now that you’ve become a ghost?”

The woman did not look up.

“No.”

“Do you feel the need for revenge on the person who killed you?”

“No.”

“Have you ever haunted anyone?”

“Yes.”

The woman did not ask her to elaborate this time.

Another butterfly landed on the woman’s ear. This one was pale pink. It was the same color as the lilac bush by her mother’s cottage, before she’d died and it was sold, and Adaline had left to become a lady for her cousin.

The woman did not ask her if she liked being dead. She did not ask her if she knew of any other ghosts. She did not ask what Adaline had done when she was alive, or if she had had any friends or lovers, or if death was fun, or boring, or just okay.

“Thank you for your time, that will be all.”

The woman stood, bowed, and left. The butterflies did not follow her through the door.

Two weeks later, Adaline found the story in fine print on page 8 of the magazine. It told a tragic story of a beautiful lady who saved her cousin from certain death by gunshot at his birthday party and paid the price. It told of a thunderstorm funeral and watching helplessly as her cousin was shot, as his life fell apart without her in it, the parking lot overfilled with the people who’d loved her. Adaline smiled now. She was not disappointed. She was not angry. She felt nothing at all, as if the nothingness that flattened the woman’s eyes had slid into her; slow, cold, pale, like frosted glass.

OONA MCPHEARSON is a student at United World Colleges in Montezuma, New Mexico.

This story won the youth category in the 2024 Blue Hill Maine Literary Arts Festival and appeared in Stonecoast Review Issue 22.

Photo by Simon Abrams