Stonecoast Review

The Literary Journal of the Stonecoast MFA

Fingers, Penny, Pocket

By Calla Orion

a.)

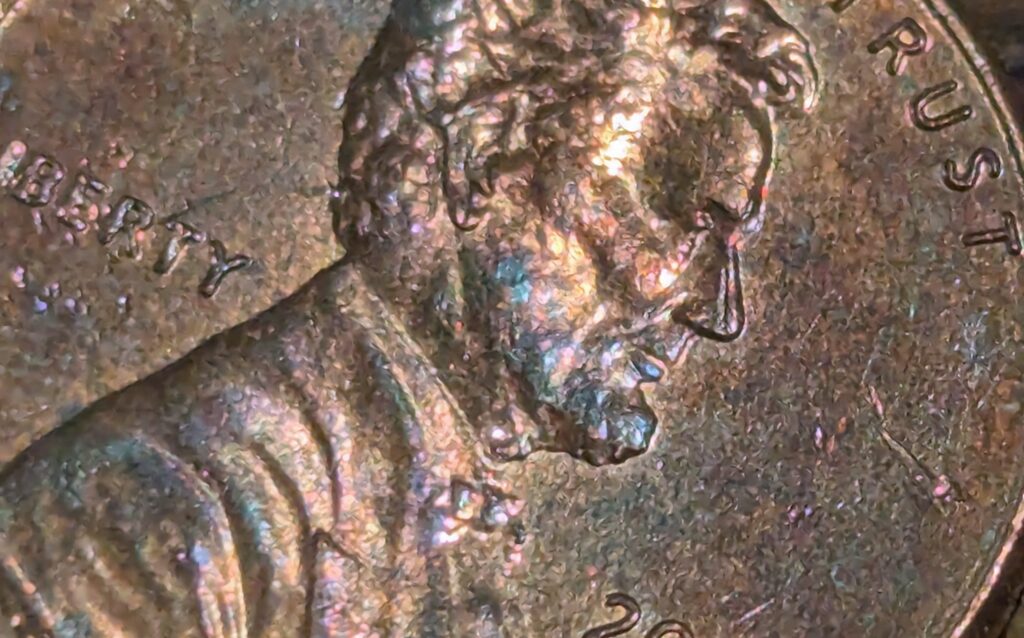

She is Fingers. Actual fingers. Bending at the knuckle to grasp a penny on the concrete; lifting back up. Penny shines in the light. It is midday. Wealth hits her in a glint that reflects into the shop display ahead. A hundred-dollar dress, fabric in drapes of raspberry golds and greens. She turns to the door. Bag shifts in hands, rustles with objects inside. She is Fingers. She holds the penny out ahead of her like a relief painting. She will give the penny away. Someone will get the penny. Someone will give the penny away. Everything works this way. The world is commodity. She is Fingers, is a commodity.

They took photos of her once. Professionals with cameras paid by marketing gurus and diamond dealers. They take no photos of her now. One time someone did, on accident. A father with his head up (rare), eye chasing, hand tracking, a child on a wild tear. She sat in the foreground, whorl fingerprint smiling into the lens. This habit. Her gaze little missed a rounded glass. She loved the way her eidolon swept into the black hole of the sensor. What happened to her then? Did her body-as-light die on entrance? Submitted so fully into bits?

She modeled rings. Twisting knots of (ostensibly rare) glimmering metal and diamond. Saturated by daylight-blue metal halide to highlight the fidelity of the cut. Faces that divine, instill spectacle. Her skin tanned from fair. She made herself into belts of hope, wrapped into loops that she clamped around her waist. Now she feels that recursion as a tangible thing, how a snake coils around a prey. Past is present. She presents her Penny.

#

b.)

Penny moves forward. He knows no other dimension. He turns, light reflects him, but he knows only one path. He went on a date with a girl once. She seemed to like him; he for sure liked her. But she handed him off to another. His heart broke. He learned to like the new person. But this new person handed him off, as well. His heart broke again. Every person he met pushed him away just as he began to grow attached.

He learned detachment. Learned not to be too invested. To extract what value he could while he had the chance, then move on before he could be moved on.

In some ways he felt lucky. He had met others much like him. Maybe not just like him (Could such a thing exist? Fantasy.), but close enough that he saw ease in his growing nihilism for the cycle of life, experienced chaotic pleasure at seeing the eventual fall of those who clung still to their idea of hope. That downturn inevitable; their own fault for not conforming to the cynical Fingers’ economy.

Some he met had known long relationships—a 1976 Bicentennial Quarter kept in pocket or palm as a totem of optimism—but were invariably lost or their lovers died. Others were much older than him, had lived long, hopeless lives similar to his own. Some suffered grotesque, bleaker fates, their faces caked in black gum. They grew unfamiliar even to themselves, and came to lose their function, worth only what precious metals composed their form. He once knew a 1943 Wheat Penny who went from sweet glossy seal to stained on the sidewalk in a matter of days.

Stories got passed around that if you lived long enough, showed the right face from the ground, stayed clean and unique, you would be clamored for. Live forever in perfect and perpetual hermetic grace. That could be the ultimate end.

But nobody had a sure-fire path for achieving it. It seemed up to the essential state. A random walk. Because, as it looked from the outside-in, even the most perfect ones in imperfect hands could become landfill.

All this passes through Penny as he moves with Fingers. Particles of mind drifting along, smaller even than light, sift through him as Fingers and Penny sink into Pocket.

#

c)

Pocket started life sewn inside out, and had to be turned inward. Fingers and Penny fit in Pocket quite well, with room to spare, in fact, and sometimes more friends do arrive. Gum Wrapper, Paperclip, Key-on-a-ring. Sometimes it feels like a party. Sometimes it’s too much.

Pocket understands the transitory nature of Things. It transmits, transmutes, transfers. It understands that sometimes things are in it, and sometimes they are out. Sometimes it is filled up far beyond its natural capacity—with the fullest extent of the universe in which it exists—and sometimes it is entirely hollow.

It is Pocket’s life duty to hold inside all it can. This it does in love. It has no urge to keep in perpetuity, nor does it feel it should, but those that do stop in deserve safe passage. Even when it can feel pressure at its seams, full with the intrusions of its life’s work, Pocket contains what comes. There is a reward in the ache, and in the relief of ache’s ending.

Fingers leaves Penny in Pocket. Pocket holds Penny, wraps Penny with its fabric, allows him to dance, to toss about and leave small traces of self. Pocket cares for Penny, but in the way a ferry floats for its passengers. Availing all of itself to the service of Penny’s transit. Fingers comes to retrieve Penny and take him away.

Pocket knows that one day, the stitching that holds it together—that allows it to serve its purpose—will one day fall apart. In a way that even Fingers could not sew back together. Pocket knows that this is all a matter of time and the ending of cycles. Until then, Pocket will do as a Pocket does.

CALLA ERIS ORION is a mirror in droste; looking out at the world as a reflection of oerselves reflected back on oerselves. Oe spend as much time sleeping as possible, though don’t get nearly enough sleep. Someday, oe’ll be able to get the ideal amount sleep a night, somewhere in the region of 20 hours. Oe work at a small liberal arts college in Maine, live with oer dog Copper, and increasingly enjoy solitude. Sometimes oe write music, sometimes oe make video games. Most of the time oe’re trying too hard to relax.

This story originally appeared in Stonecoast Review Issue 21.

Photo by Heather Jones