Interview

What do you write?

I write whatever I’m inspired to write at the time—science fiction, mystery, fantasy, literary mainstream, social commentary, non-fiction—in anything from flash to book length.

Is there an author or artist who has most profoundly influenced your work?

Almost every book I read affects my writing in some way, sometimes showing me what to do, and sometimes showing me what not to do. Choosing one author? Maybe C. S. Forester, because the Horatio Hornblower series stirred me to write in the first place.

Why did you choose Stonecoast?

Primarily, it was the instructors, but it was also because of the flexibility in the program. I am taking fiction workshops and popular fiction workshops, and I could have taken poetry and creative non-fiction workshops if I’d wanted to. The seminars given at the residencies are available to anyone who wants to go, so a student doesn’t have to stick to their genre.

What is your favorite Stonecoast memory?

The student readings. Some of the pieces students read are funny, some are profound, but the best are the soul-baring, true stories or memoir snippets, because they are much more powerful when read by the author, and because these intimate stories demonstrate how much we students trust the Stonecoast environment.

What do you hope to accomplish in the future?

Assuming you mean from a literary perspective, I’d like to have a lot of people enjoy my books. I’d also like to teach more writing workshops in the future. I find workshops educational for everyone involved, including the workshop leader.

If you could have written one book, story, or poem that already exists, which would you choose?

Well, my own published book I suppose, but if you mean a book by someone else, I can’t imagine. I don’t understand the “I wish I’d written that book” concept. It makes no sense to me. If I was forced to choose one book, though, I would choose Several Short Sentences About Writing by Verlyn Klinkenborg. It’s a brilliant, concise book about writing great sentences. I figure, if I’d written that book, then I would be able to consistently incorporate everything in it into my fiction writing. On the other hand, if I’d written Harry Potter, I’d be rich right now, so there’s that.

Featured Work

Walking Shadow

Walking Shadow is a science fiction noir mystery set in a near future Chicago where the surgical forgetting of bad memories is commonplace—and Benny has forgotten something dangerous.

The following are the opening chapters of Walking Shadow (Grand Mal Press, 2012, available everywhere in e‑book, hardcover, paperback, and audio).

https://www.amazon.com/Walking-Shadow-Clifford-Royal-Johns/dp/1937727254

http://www.audible.com/pd/Mysteries-Thrillers/Walking-Shadow-Audiobook/B00CH4VZ92

Chapter 1

I knew I’d had some memories removed. I could tell because the removal company sent me payment-overdue notices every week.

I had just received another such bill, and this one was especially demanding, implying some unspecified action would be taken to recover their funds if I didn’t pay immediately.

I wondered what memories I’d had removed. Had I killed someone? Had I seen some grisly death, or had an astoundingly bad breakup? Had a doctor told me I had only three months left to live? Forgetting was a drastic response to a dramatic event. What was my dramatic event? I lay in bed in my tiny apartment, staring at the ceiling and reviewing my history, trying to find the holes. It was sort of like trying to discover the hiding place of a needle in a haystack after I’d paid to have the needle removed.

When my PAL said, “Hey, it’s eleven-thirty,” I shook off speculation about my past, rolled out of bed, and dressed to go meet my brother Arno at Socko’s restaurant. I had lunch with him every Wednesday at noon.

I didn’t have a car, and the buses just didn’t go that way. My brother did have a car, but refused to drive over to my part of town. He worried that the neighborhood kids, who would promise to protect his brand-new Moto-400 for a little pocket change, would instead strip it of everything and leave just the trackerID chip and the front axle lying in the parking space. I walked.

On the way out of my apartment building, I said hello to the doorman, a crusty, gray bum wearing two overcoats and three hats piled on top of each other. That day, the hat on top was a once-white knit with a pompom dangling from one thread. He sat huddled against the entry way, out of the wind. It was his real estate. No one else ever sat there. He looked back at me, but didn’t move. I wasn’t one of his patrons.

It was a cold, gritty day in Chicago, much like the day before. Dark-bellied clouds lumbered past overhead, threatening a numbing fall rain. I shuffled south on LeSally Street, my jacket collar turned up to the wind, my thoughts turned inward to my memories.

As I walked along Diversity, dodging the land traffic, and closing my eyes against the dirt storm whenever a buzzcar lurched by overhead, I thought again about the bill I’d received the evening before. Forget What had sent me bills every week for the last month. According to them, I’d paid two thousand in bad money to “remove a memory or series of related memories.” But I couldn’t remember.

Of course, I hadn’t seen money like that in years, and if I had, I sure wouldn’t have wasted it on a forget. I would have spent it on something tangible—something that would have been repossessed if I left a bad money trail. Forget What couldn’t reinstall a forgotten memory. Service had already been rendered.

The letters referred to me as Sir, but the computer that generated the impersonal mail really meant deadbeat—I could tell. I could feel the smirk embedded in each one.

Okay, so I blinked them. I blinked lots of people. Most didn’t bother to complain, because they didn’t want to admit they’d been taken, or because their accounting was so bad, they didn’t even realize they were out any money. Forget What didn’t seem to be willing to forgive or forget. They actually wanted their money. But if I’d paid in real money, they wouldn’t have bothered me, and I would never have known I’d had any memories removed.

I crossed Hacker Drive and ducked into the Sliver Building. The real name of the building was The Silver Exchange, but no one called anything by its right name anymore. The Sliver looked like a Bowie knife sticking up out of the ground, as though someone inside the earth was trying to cut his way out. I went in through the 4G delivery entrance in the hilt, where the couriers delivered packages. Going immediately through a door to the left into the dock area avoided the security guard. I said, “Hey,” to a flat-faced blonde girl, as though I knew her, and strode through the piles of pallets and boxes, scanning for a small box I could take with me. I didn’t see anything sufficiently portable, so I slipped through into the catering area, then into the atrium and out onto Crackson. It was a useful shortcut, and the more I used it, the less likely anyone was to notice I wasn’t supposed to be there. I also avoided the overhead transit stop where police tended to loiter.

People pay to forget stuff that traumatizes them—memories that haunt them, that pull at their lives and bend the flow, memories they don’t want to deal with in an honest way. Like Wilde said, “No man is rich enough to buy back his past,” but now, at least, people who had the money could pay to forget what they had done. Walk in an emotional wreck. Walk out a new person. Consciences cleaned while you wait. If you were rich, you could be happy. You could steal, cheat, and bribe your way to wealth, then forget everything you did to get your money, forget everyone you ruined, forget everyone you took advantage of. Forgetting is better than a priest giving you some penance and telling you everything is forgiven. Forgetting is true absolution; the guilt is surgically removed.

Socko’s was one of those small, steamy, mostly takeout places that has astonishingly good food served on flimsy plastic. The padded vinyl seats were as old as the building and just as hard. The people there treated you like they were doing you a favor by allowing you to eat there. I ate there a lot.

Arno was at a corner table facing the entrance. He waved as I pushed through the revolving door, but then went back to reading the paper he had tucked above his plate. I stood in line behind a woman with no hair and two kids, then ordered a beandog, asparagus sticks, and a citrus from a thin man with no eyebrows who wore a magenta plastic hat. I hadn’t seen him there before. He had a tattoo of a beard on his chin and wore a Socko’s shirt. “Say,” I said, “do you have hair tattooed under that hat?”

He tipped his hat to me. There was another hat tattooed on his head. It looked like a bowler. It was blue. “One for every occasion,” he said. His blue tattoo turned orange, then violet, as he turned to get my order.

When his head turned blue again, I took my beandog and joined Arno.

“You’re late.”

“Hello, Arno.”

“What were you doing this morning?”

Arno was like that. He seemed to think that just because I was late, I must have had something better to do, but the walk was twenty-five minutes, and it usually varied by five or so. I ignored his question.

“I got a bill from a forget company,” I said, thinking to change the subject as quickly as I could. “They say I owe them for a forget.”

“And you blinked them, right?”

“I guess so. I honestly don’t remember. Do you know what I forgot? I must have talked to you about it before I had the memories removed. What was my pain?”

“I dunno,” he said. “You don’t talk to me about that stuff.” He quickly went back to reading his paper, but I had the feeling he knew, and wouldn’t tell me.

My brother was tall, with thick black hair, and he worked out, though at his house, I’d only ever seen him sitting on the machines, not pushing or pulling or lifting, but that’s enough for guys like him. He looked fit and healthy, well fed, but not loose. His hands were steady and muscular. We didn’t look at all alike. I was just a little shorter, but had sandy hair and a thin wiry build. The only reason I was physically fit was that I had to walk everywhere.

“But didn’t I talk to you about it at all?”

“Don’t think so.”

“Would you remember if I had?”

He stopped eating and stared at me for a moment. Doubtless this was the very look he gave his employees that would make them work overtime without pay. “Probably not,” he said. “You so seldom say anything of interest.”

That’s all I could get out of him. He folded his paper and started talking about what kind of job I should be looking for, and how I should think about my future and not my past. While he talked, I considered Forget What, and decided I should go to the removal place and talk them into telling me what I’d forgotten. I think I said, “Uh huh,” a few times, and I kept my eyes trained on his right eye, so he’d think I was taking him seriously. Meanwhile, I chewed on my asparagus sticks and my thoughts.

The forget companies were secretive about how they did forgets. It wasn’t something that had been exposed by the press, but there were a lot of rumors about it. I’d heard that to remove a memory, they evoke the memory, which is usually so terrible that it gets you all worked up, then they scan your brain looking for spots of high activity other than the places that were active in similar memory recalls. When they find the spots that are unique to this memory, they insert a long, thin wire with a small loop on the end, then they spin it, scrambling up your brain at those spots, and you forget. That’s how they used to do lobotomies. They would insert the wire up under your eyelid and mush your frontal lobe. The more expensive forget companies used lasers or crossing sonic beams or something, but I have to admit, I was too cheap for that, even when I used fake accounts.

When Arno finished eating he said, “I’ve never understood why you would pay to forget a part of your life. It’s like paying to become someone else. It’s pretty close to death, if you ask me. It’s not as though you get to go back and try the forgotten event over again. Part of you is just gone. You just come out a different person.” He looked at me hard, like he expected me to say something.

I swallowed the last bit of beandog and leaned back. “I really don’t remember doing it, Arno.”

“Benny, maybe this is your chance to change yourself. Obviously, you did something so abhorrent you couldn’t stand yourself, and you had to change your past to reflect your own self-image, but you’re really not that nice a person. You’ve got no job, no woman, no friends. You live by the dole, Benny. Bums live by the dole. Idiots and nuts. You’re not stupid, and you’re not fundamentally lazy. I know jobs are hard to get, but you could at least try.” He sat back, apparently exasperated, yet I sensed an inside joke. I had a feeling he’d given this exact speech to me before, but I wasn’t sure of it. Somehow, he found me amusing, and that irritated me more than his boring lectures.

In any case, I couldn’t figure out why my lack of a job bothered him so much. I never asked to stay with him and his wife. I didn’t ask him for money. I wasn’t a mooch. I thought he viewed me as a tarnished spot on his shiny public image, a pit in his chrome, but I couldn’t see how I was holding him back. And, anyway, I considered myself retired. I really didn’t want to work. I’d just waste the money on a few gadgets, or some real food.

“Maybe I could be a car thief,” I said.

“Maybe you could be a little more serious.” Arno was a real brass pipe.

“All right, maybe I could be a buzzcar thief.”

Arno was annoyed, but he smiled anyway.

“OK,” I said, “who would give me a job, Arno? Like you say, I don’t know anyone important, and certainly not anyone important enough to have control over hiring. I know a few people who could get me a job stealing stuff, or selling stolen stuff, but real business types? Suits? If I came to you and you were a hiring manager, would you hire me?”

“I’ve hired you before, Benny,” Arno said, looking at his watch. “I’ve got to meet somebody in ten minutes, but think about what I said and try to remember what you’re good at. When you do, come see me.”

I couldn’t remember being especially good at anything in particular, and I couldn’t remember working for Arno. It seemed like a bad idea to work for family. They would think they were doing you a favor, and they would expect something in return—something more than just a day’s work. And you couldn’t quit, because they had spent this effort on you, and they would think you had quit them, not the work. I didn’t think Arno would take kindly to me quitting on him.

When Arno stood, I noticed he had a bit of green chili sauce on his white shirt. I didn’t mention it. I ate my last stick and left.

When I returned home, I looked at the bill again. The removal company had included a netdeposit address, but no street address, and, of course, I couldn’t remember which Forget What clinic I’d gone to. There were over a hundred facilities in Chicago, seven or eight within easy walking distance. I probably went to one of the closer ones, but there was no way to know, and none of the people at the clinics would be willing to admit to being the source of my problem.

I sat down at my table and wondered if I’d actually had any memories removed at all. How would I know? I didn’t remember having any memories removed, but the letter that came with the bill said I wasn’t supposed to remember anything about the removal session, that’s why they could guarantee it. They give you careful instructions on how to pay them, so you don’t notice the debit later. They short-circuit your short-term memory and put you out on the street. You don’t even remember having the procedure, so you don’t go looking to find out what it was you forgot. But, apparently, I’d given them a false netdeposit path, and the money was later removed from their account. You’re supposed to pay in advance for obvious reasons, but they claimed I’d cheated them.

Which I could believe. I could see myself doing that. I’d figure, hey, what could they do? It’s not like I actually had that much money, or even the likelihood of getting that much money. I was on the dole and likely to stay that way. I was retired at thirty-one. I was a free man.

The forget still nagged at me, though, and I realized I just couldn’t stand it. It was a tickle, and I knew it would soon be a ferocious itch.

So, why be so stupid as to go looking to remember something I’d worked so hard to forget? Because I’d felt empty of late, passionless and listless. I went to the dole every week, had lunch with my brother, bought groceries, slept, pilfered when I needed to, worked odd jobs once in a while. I was walking along through my life without really thinking about it because I’d thought my life had always been that dull.

But Forget What kept reminding me that before September there had been something more, and I’d purposefully removed it. Whatever I’d forgotten had left a bigger hole than I must have expected it to. I stared at the wall, trying to remember, though I knew I wouldn’t be able to.

I heard the vator doors open and close. The PAL in the next apartment played old Russian piano music. A pigeon landed on my windowsill high above my bed. I wrote “Dust me” on the wall with my finger.

I decided to let the issue slip for a while, figuring that if, back in September, I’d wanted to forget, I should trust my own decision. So, I tried to avoid thinking about it. I tried to imagine the forget never happened—that Forget What was actually blinking me, that I was the victim.

I watched some avatar fighting. The sport wasn’t what it used to be. The teams were allowed to put too much artificial intelligence into the avatars, so the people controlling them were no longer hired for their ability to fight in the virtual world, but more and more as entertainment for the audience before and after the match. They were sharp, pretty people instead of the tough, real fighters who had competed before. The whole sport had turned slick.

The forget-the-forget strategy wasn’t working. While I was in the bathroom trying to review my past and spot the hole in my memories, my PAL beeped at me. I yelled to it to read the mail out loud.

The message came from Forget What. They said they had completed a review of my account and decided that if I didn’t pay up within three days, they would inform the police about the memory they’d deleted for me.

The police? My heart stopped, while a list of hiding places shot through my mind. What kind of memory had I had removed that would interest the police?

Chapter 2

The police are okay if you’re clean and working. But, for the rest of us, the legal system is quick to use the memory lasers based on a psychologist’s recommendation about which childhood memories caused your current criminal schtick. They can wipe your whole childhood, wipe your memories of committing crimes, and wipe your memories of friends and associates they believe might be harmful to your future. It saved them a lot of money they would have had to spend on jails. Since I couldn’t remember what schtick I forgot, I expected that, if they caught me and convicted me of something, they might turn all my memories into pâté, just to make the public safe.

I hunted down the first bill Forget What had sent me, looked at its date, subtracted a day, maybe two, for them to figure out I’d blinked them, and decided that whatever I’d done, I probably did it before September tenth. Thinking back, I couldn’t remember much from that time, even though it was only a month or so earlier. Late summer, early fall tended to merge into one continuous highway. A few events stuck out—the eight-day rain, the day the fire melted Jummy’s, the day I spent with Jolie. But, for the most part, there weren’t many lumps in the pavement.

I printed a copy of the last bill, put it in my pocket and went to Reborn Street to see Chen. I remembered being on Quacker Street with Chen on the eighth. I knew it was the eighth because I’d had to go to a gov clinic and get my finger bandaged that night.

Chen was the only person I knew who I thought might do something while I was with him that I’d want to forget all about. He’s an ass-thatcher for fun. He comes up behind a guy and lasers his ass with a preprogrammed laser etcher. He just pops it out of his pocket, focuses the targeting beam on the middle of the crack of the guy’s ass and ticks it. The laser flashes around the guy’s ass for about a tenth of a second, and then there’s a lot of screaming and hopping up and down. I laughed thinking about it, then realized I would never purposely forget something as funny as that. I felt a pulse of guilt about the thatching, but Chen was good at picking out the most pretentious and pompous men from the crowd. Then I imagined the hospital write up, “Removed intricate drawing of Tweezy the Bumblebee from guy’s ass.” Tweezy. Chen was a whirl.

Reborn Street is near the Rocky Roads Expressway, right where it enters the new Chicago Automated Transit switching tunnel, about a fifteen-minute walk. The noise from the CAT trains there was thunderous, but the rents were low. Chen had a flat in the old United Nations World Police building, now called the Unapartments. It was all concrete with high narrow windows, and two large restaurants flanking the entrance like a pair of brown shoes poking out from under a ground-length, concrete trench coat. They had painted the building blue in hopes of making it look less institutional and less military. It helped a little. A painting of a twenty-foot, twirling, kick-boxing bear in boxer shorts and sunglasses worked better, but the owners had painted over that not long after the artist created it. I still missed the bear. He’d always made me smile.

You never walked straight to Chen’s. He had some odd rules. I took the vator up to seven and over to cross thirty-two. Side-slide vators make me woozy, but it only lasted a minute. I walked slowly back down two flights of stairs to Chen’s door.

Chen wasn’t there, but Paulo let me in. “He’ll be back in a tick,” Paulo said. He winked at me, just like Chen always did, but I didn’t wink back. “How ‘bout you come in and sit? Wait for him. Like a derpal?”

“No, thanks,” I said, and took a chair in the music room.

Paulo was a small, no-fat guy who moved in short staccato bursts like a helper bot, but without a bot’s focus or clear intent. My name for him was Brownian Motion. He wore an apron, presumably with something else on underneath, though that wasn’t obvious. The apron showed two bibbed lobsters holding skewers and grinning. Grinning lobsters. Grinning lunch. Might as well have a smiling cow flipping real-beef hamburgers.

I sat in the music room and stared at the painting of Lena Horne, which Chen had paid an out-of-work artist to paint on his carsicord. He never learned to play the thing, but he liked Lena, so he kept the instrument pushed backward up against the wall to display the painting. Chen liked to listen to her old recordings, and I’d acquired a taste for them as well.

Paulo was in the kitchen making dinner and noise. The apartment smelled like ginger and tomato sauce.

“Hey Paulo, you got any beer?” I yelled.

“Nah, just derpal.”

I didn’t drink derpal. I hadn’t acquired the taste, and since it’s illegal, I didn’t want to. In any case, I didn’t want that much bliss from a bottle.

Paulo stuck his head around the corner. “What brings you over here?”

“I got this bill from Forget What, and I wanted to talk to Chen about it. They’re getting cranky.”

“Oh!” Paulo ducked back into the kitchen. I heard some frantic stirring, metal on metal, then he yelled, “He should be back soon.”

Beside the carsicord, I noticed a new decoration. It appeared to be a regular aquarium at first, but the fish turned out to be engineered to look like tiny people swimming around in the flow from the water pump. Their little faces looked frantic, as though they needed air, though of course they didn’t. They came up to the glass begging me for something, but I didn’t know what.

Chen came home then. He stopped by the kitchen to kiss Paulo and get a derpal, then walked into the music room. “What are you doing here, Benny?” Chen said warily.

Chen was a little shorter than me, and just as thin, usually. He had straight dark hair that day, and a wide belligerent nose, which didn’t match his close-set eyes. He must have been wearing padding around his waist, because he looked a bit chunkier than usual. He walked with a swagger that was so dramatic it looked a bit silly.

“Yeah, it’s good to see you, too,” I said. “Maybe I should just go.” I stood up, but didn’t start walking.

“Oh relax, Benny. Why are you so touchy? You got so many new friends now, you can afford to walk out on your old ones?”

“What did we do the last time I was with you?” I asked, sitting down again.

“I’d prefer to forget all that. At least, I will if you will. I bought a new gun. Want to see it?” He pulled what looked like a kid’s space-blaster out of his coat pocket, handed it to me, then went to hang up his coat.

The gun was real enough. I’d expected a slap gun, one that shot what amounted to a slapfaint, which made the victim faint and stay out for an hour or so. I popped the clip. It had room for fifteen bullets, but contained only three.

Chen came back. “What do you think? Doesn’t it look famous? Just like a toy. I could walk down the street with that in my hand and no one would take notice. You want a derpal?”

“No, thanks, and they would notice, Chen. The police know about these, although they’re usually green rather than yellow. Green’s a bit more subtle.”

He looked around the room thoughtfully. “Where should I keep it?”

I told him that if he was worried about intruders, he should hide it in the bedroom somewhere. If he was worried about guests, he should put it at hand, next to where he usually sat.

He sat down, then slid the gun into the drawer of his side table. Bright yellow, goofy-looking plastic body wrapped around a businesslike gun. Very Chen.

“So, what did we do the last time I was with you?” I asked again. “I mean other than the fist fight. After that. Did I leave right after that?”

Chen was still looking at the drawer, smiling. He liked his new toy. He sighed and looked at Lena as though for guidance. “Yeah. Fist fight. Beating you mean. You were pretty mad about me thatching part of your finger. It wasn’t my fault. You moved.”

“I know, but did we do anything together after that?”

“No. You ran off saying you had to go to the hospital. I haven’t seen you since. It was just a nick.” Chen stood, paused for a moment, then walked over and put on some low music—Lena singing “I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues.”

I pulled the Forget What bill out of my pocket and showed it to him. “I’ve been getting these letters from Forget What. They say I had a memory removed, but I don’t remember it. They say if I don’t deposit the money, they’re going to tell the police about the contents of the memory I had removed.” I watched him for a reaction.

“I wouldn’t worry,” said Chen, looking a bit worried. “Maybe you never had a memory removed. Maybe they’re just blinking you. Could be they always do this when they’re low on trade. Gov isn’t real happy about the commercial forgetters anyway. The Senate is trying to pass a law that would require the police to attend every forget, and have the forgetter pay for their time and expenses. And anyway, the fact that you’ve had something forgotten isn’t admissible evidence. There’s no telling what you forgot. Of course, it might be admissible if the forgetters kept records, maybe even video, of the whole thing.”

“Can they do that? I thought it was confidential, like talking to a priest or something.” I watched a little fish person get temporarily sucked down against the gravel bottom of the tank where the pump intake was.

“I don’t remember hearing about the use of forget information at a trial before, but they probably keep that kind of thing quiet. What did the contract you signed say?”

“Contract?” I couldn’t remember my session, so of course I couldn’t remember a contract.

“I bet they record all the sessions.” Chen said, sighing back into his chair. “They replay the removal session in court, then what?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Then what?” I looked at my feet. Chen wasn’t helping at all.

Chen yelled, “Hey, Paulo?”

Paulo danced into the room waving a large spoon.

“Doesn’t Carla work for Forget What?” Chen said, with an odd leer. “She could probably get a transcript of Benny’s last forget session, right?”

Paulo glared at Chen like he had said something tactless. He lowered his spoon. “Yes, yes she does,” said Paulo stiffly, “but I don’t think she can help with that. She’s a busy person.”

Chen winked at him. “Sure she can.” He turned to me and added, “Paulo will give her a call later.”

Paulo wasn’t happy with the idea, and I can’t say I was overwhelmed either. Chen’s friends generally weren’t reliable, but I couldn’t pass up the angle. Especially since friends usually work for free.

Paulo abruptly retreated to the kitchen. Chen smiled at me and took a long swig of his derpal. “Hey, you want to go over to Quacker tonight? Jon Tam built me a new thatcher. It cuts a picture of a rabbit diving down the victim’s asshole.”

Chen started laughing and couldn’t stop. That started me laughing. I couldn’t even imagine what that hospital write-up would say. “Sure,” I said, “just keep that thing pointed away from me.”

Chen laughed hard enough to snort, and started wheezing. He had to rip off his fat, fake nose to get more air. He held it in his fist with the tip jutting out between his index finger and his middle finger. “I’ve got your nose,” he said, then rolled onto the floor with tears in his eyes, unable to speak.

Whatever Chen did for money, I figured it must be stressful.

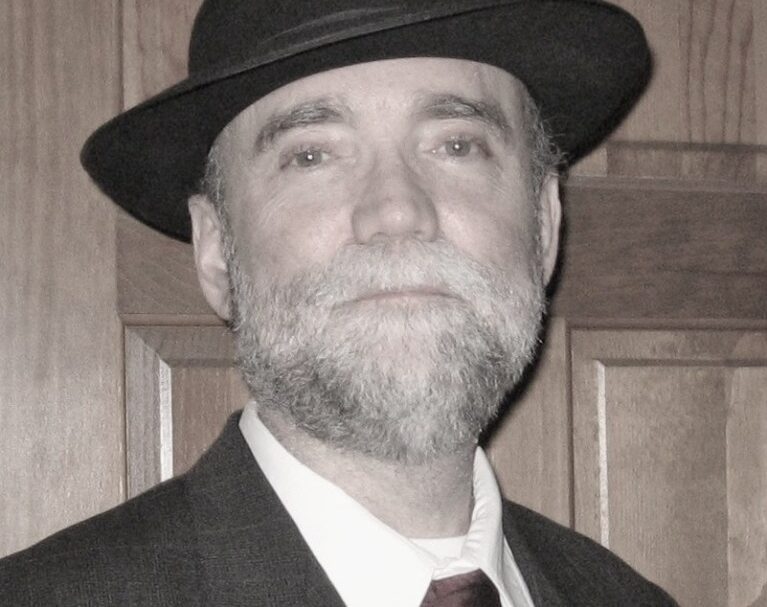

Clifford Royal Johns spent many years designing integrated circuits and computer-aided design software, all the while writing fiction when no one was looking. He has an MS in Control Engineering, and an MS in Written Communications.

He has now dropped his engineer hat to focus on his fiction, and is working on his MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast program. Although Cliff has published numerous short stories, and a science fiction/mystery-noir novel (Walking Shadow, Grand Mal Press, 2012), he believes that if you’re not actively learning, you’re doing something wrong. Cliff writes science fiction, fantasy, mystery, literary, humor, and most things in between.

Cliff hails from the Chicago area. When he’s not writing or reading, he likes to build furniture, bale hay, go boating, do crossword puzzles, timber frame, rescue dogs, and play blues harmonica—generally not all at once.