Interview

What do you write?

Short stories about loss, family and growing up; short stories about goblins, superheroes and post-apocalyptic vampire-ridden militaristic societies; YA dystopian novels about teenage princesses and secret agents running around saving the world. One-minute plays, which are fun and ridiculous and smash writer’s block. Try them!

Is there an author or artist who has most profoundly influenced your work?

Definitely not one. Leo Tolstoy and Alice Munro have most profoundly influenced my life. Junot Díaz and Liane Moriarty, because they’re hilarious, genuine and dynamic. Robert Jordan, not by choice–I reread Wheel of Time throughout junior high.

Why did you choose Stonecoast?

The opportunity to tailor your studies to your interests, work across genres, and do popular fiction; the emphasis on social justice and writers’ responsibility to create positive change; and the Ireland residency (can’t wait!). And I have a coworker who got a maniacal gleam in her eye when I asked about her experience here.

What is your favorite Stonecoast memory?

Sitting by the fire at the Harraseeket, starting to sing “Just Around the Riverbend” from Disney’s “Pocahontas” to make some point, and hearing the person across from me join in — then the person next to her, then the person next to him. Everyone knew every word and modulation.

What do you hope to accomplish in the future?

To write stuff I’m proud of, that says what I want to say, that some number of people enjoy, that is helpful in some way. To better understand mind and imagination and push the edges of what’s possible with words. To help people find and tap the healing, transformative power of writing. Also to open a beer bottle on a countertop.

If you could have written one book, story, or poem that already exists, which would you choose?

I feel like I can only love the works I love because I haven’t written them! Maybe Ulysses, so I would have a clue what it’s talking about.

Featured Work

Rotten

The following is a work of fiction exclusively for Stonecoast Review.

Usually Jaron’s got one wrist on the wheel and the other hand drumming a samba beat as he warbles off-key about a mangled muskrat in the gutter who just wanted to see the stars. But tonight he’s sitting up straight in his good blue shirt, collar so crisp it could cut your finger. His hands are clenched at ten and two.

“We’re late,” he says.

The clock in the dash reads 5:48. “Didn’t they say six?”

“You don’t know them.”

We roll down a narrow driveway paved with white stones to a huge house surrounded by pitch-black woods, park and get out of the car. The garage door rises, revealing two identical Porsches and a man with carefully combed, silver hair wearing glasses on a chain. He walks toward us. This is when Jaron would normally start humming the Darth Vader theme. Instead, he shoulders past me, reaching for his dad’s hand. They shake. Jaron grips hard and claps his dad’s shoulder.

“How’ve you been?” he asks, sounding so hearty that I look around for the audience before realizing he’s not hosting one of his Sunday afternoon puppet shows.

Jaron’s dad lets go first. “Oh, I’ve been all right,” he says. His voice is mild and warm. Light gray eyes crinkle behind his glasses. “Threw out my back again last week. But that’s my own fault for taking on that beast.”

He nods toward a dark shape by the driveway and winks.

It’s a stump that’s been half uprooted—enormous, ugly, mutated-looking. The top, a roughly chopped circle, is old and dead, deeply cracked and bleached pale. But the roots, startlingly large and dark with fresh dirt, appear alive. For a second I think I see sunken eyes, a tumorous nose, and a gaping mouth in the warped wood.

“I’m Gavin,” Jaron’s dad says to me. “Pleasure to finally meet you.”

“I’m so glad to meet you, too.” Making sure to smile, I hold out the peace lily in the square vase I picked out at Floral Arts when Jaron said we needed a gift. “I hope we’re not late?”

When I say “late,” Jaron stops looking at the stump and shoots me a look like I killed his dog.

Gavin’s bushy gray eyebrows go up. “You’re quite early,” he says. He takes the vase and waves me into the garage. “Thank you, these are gorgeous.” We follow him up the steps and into a living room with a vaulted ceiling and a crackling fire. “Floral Arts?”

“Jare-Bear!” someone calls from the door to the kitchen.

A woman wearing a tie-dye apron over a bright blue dress floats into the room, arms out, doing a rapid little shuffle.

“Oh, yeah? We doing one of these?” Jaron allows the hug, but when she starts to dance with him, he holds her at arm’s length. “You okay there, Mom?”

We head into the dining room, where polished glass cases display swimming and soccer trophies with Jaron’s name on them. There is a lacquered liquor cabinet with no liquor in it. Gavin pulls out a chair for me at the gleaming oak table. Jaron’s mom, Pam, gets so excited about the fact that we both do hatha yoga that she forgets to pour the Cabernet, then gets caught up doing impressions of the clients she advises and forgets again.

I’m waiting for the fangs to come out, but instead there’s a merry argument about exactly who came up with the recipe for the herbed meatloaf. Gavin, serving mashed sweet potatoes, asks how the music treatment group is going.

“Music therapy,” Jaron says. He talks about the crowd at the concert last night, how the guys stayed on beat, how they didn’t even need him there.

Halfway through dinner, a bang sounds from the front. Jaron and I jump. His eyes flash to mine. A second later, a tiny dog bursts through the dog door, yapping and jumping and spinning. The dog is cotton-candy pink.

“Meet Popcorn,” says Pam.

Popcorn is a terrier with her own Instagram channel. We can’t stop laughing as Pam tells us how she dyed her pink for Popcorn’s birthday photo shoot. Later, Pam pours sweet, strong coffee into tiny white cups, and I tell the uncut version of the time the neighbor’s Rottweiler chased Jaron into the Dumpster. We laugh harder—even Jaron, whose voice has finally lost that sales‑y tone.

“Honey, careful.”

She’s looking at Gavin, who is making a face, one hand on his lower back.

“Sorry.” Gavin says, smiling, and he removes his hand. Pam passes him the little pitcher of cream and he takes it. “You were saying?”

“Sorry for what?” Jaron says. He’s smiling, eyebrows raised.

Gavin glances at him. “Nothing.”

“You said sorry for no reason?”

“Oh, Jare.” Pam swats him with a dish towel.

“Tell her about the stump.”

Gavin gives him a steady look. “You know I didn’t mean—”

“You brought it up as soon as we got here.” Jaron lets the front legs of his chair hit the floor. “Tell her about it.”

Gavin’s shoulders go up, then down. He turns to me with an apologetic smile.

“We used to have this great old shade tree,” he says. “Healthy and tall, leaves thick as anything, branches out to here.” He holds out his arms. “When Jaron was a kid, we couldn’t get him down from the thing. Pam liked to sit under there and do her invoices.”

Pam stirs her coffee, says nothing.

“And?” Jaron’s still smiling.

“And it got cut down,” Gavin says.

“And?”

“That’s it.” Gavin picks up the little pitcher and offers it to me. “You never told us what your parents—”

“And nobody called the police,” Jaron says.

Gavin is holding the pitcher a little too far away for me to reach. “That was hardly necessary.”

“Right. Like the broken Porsche mirror. Like Gramma’s missing spoons.” Jaron’s smile gets bigger. “Why call the police when you know who did it?”

“Jaron,” Pam says. But she’s not looking at him.

Something bites my foot. I pull it away. The pink dog, Popcorn, leaps away too, crouching under the table, lips drawn back.

Gavin sets the pitcher down. “It doesn’t matter anymore.”

“So you’re digging up that stump for laughs,” Jaron says.

Gavin’s voice is even. “We’re putting in a patio.”

Jaron scrapes back his chair and stands up. “Then I’d better get that thing out of your way.”

“Don’t be silly,” Pam says. “Sit down.”

“It was a long time ago,” Gavin says.

“Good thing you’ve got a great memory,” Jaron says.

He crosses the kitchen and goes out the back door.

Gavin stares into his cup. Pam touches her eyebrow. I remember Jaron talking in a low, rapid voice to a member of his music therapy group, a pale, skinny boy with a scarred, shaven head and roughly bitten lips, three weeks out of detox. “Ten days, ten years, it doesn’t matter,” Jaron was saying as I pulled up. “They will always look at you like that.”

I excuse myself and go outside.

In the driveway, Jaron has his arms around the stump. His feet are braced on the white stone. He’s gripping the roots with both hands. The tendons in his neck are straining.

When I touch his shoulder, it’s trembling.

“It was rotten,” he says. His face is pale, his teeth chattering, beads of moisture on his temples shining in the light from the house—even though I know he’s not sick, not like that, not since we met. “It was coming down.”

I squeeze his shoulder. “Come inside.”

But he doesn’t answer. I don’t say anything else, just stand there with him under the black sky until his breaths turn to gasps, until the drops are falling from his chin too thick and too fast to be just sweat, until he’s no longer pulling, but falling, clinging to the stump—its one side sunk deep in the earth, its other sending raw, dark roots twisting into the air.

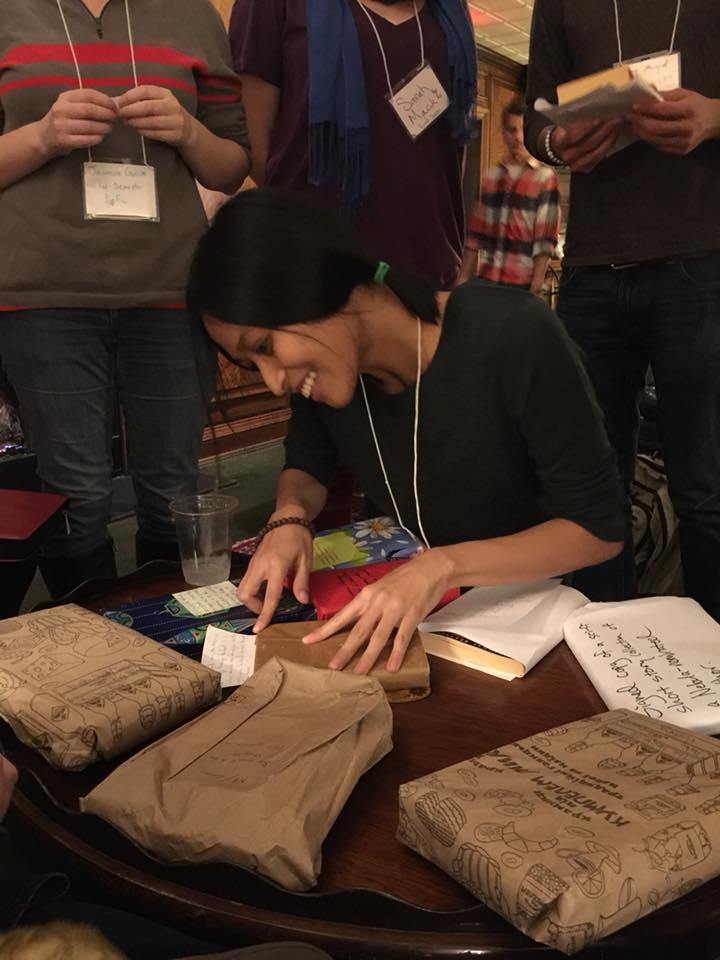

Monica Jimenez is a writer and magazine editor at Tufts University, an award-winning freelance reporter in Greater Boston, and an MFA candidate at Stonecoast. Her work has appeared in Ruminate Magazine.